The 4 Rs, and why they’re so confusing

Reproducible, Replicable… wait, which one was which again?

Trying to make sense of the four Rs

What do we actually mean when we say something is reproducible? Or replicable? Or reliable? These words come up all the time, especially when you are reading about open science or trying to make your research more transparent. They sound straightforward, but we do not always use them the same way, even when we think we do.

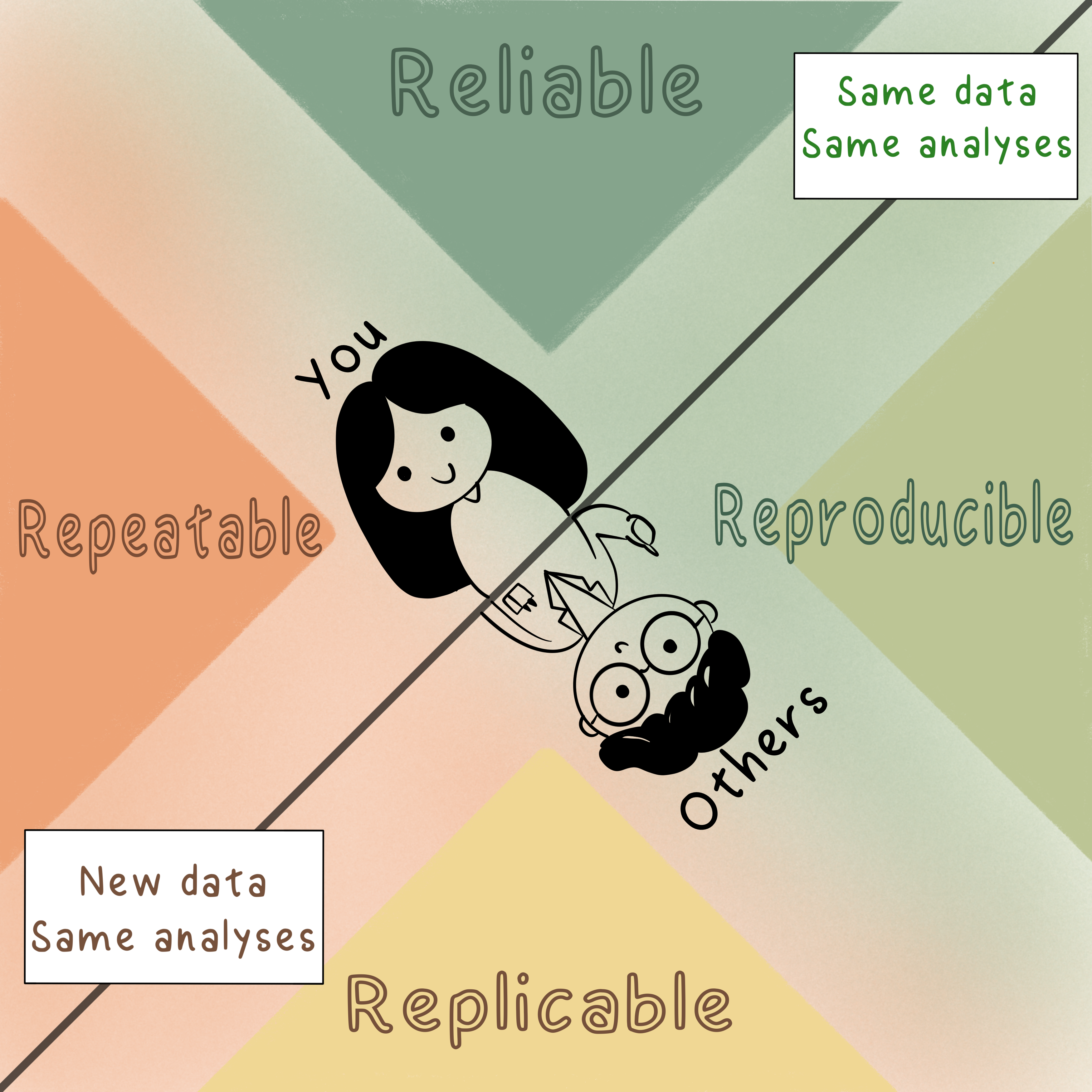

A few months ago, while preparing a talk on open science (you can find the presentation here), I ran into a familiar tangle. I had reached the part about the four Rs, and, as usual, things were a bit muddled. I did what I often do when something does not quite make sense: I made a visual. In this case, I wanted to map out reliable, repeatable, reproducible, and replicable, the way I had learned them. It was not meant to be a final word on anything. I just needed a clearer picture for myself.

In the infographic, I defined them like this:

- Reliable: when you use the same data and the same analyses and you get the same results

- Repeatable: when you use new data but the same analysis and you get the same results

- Replicable: when someone else uses new data and the same analysis and they get the same results

- Reproducible: when someone else uses the same data and the same analyses and they get the same results

In other words, these terms all ask a similar question: if we try the same process again, either with the same ingredients or some new ones, do we get the same outcome? The differences lie in who is doing the work, what data they are using, and whether the analysis method stays the same.

The moment things got interesting

A few weeks later, I attended a great workshop hosted by SORTEE, the Society for Open, Reliable, and Transparent Ecology and Evolution. It focused on reproducible data analysis in R, and after the main talk, someone posted a question in the community Slack: what exactly is the difference between reproducible and reliable?

I thought it was a simple follow-up question, something we would all agree on quickly. Several people responded. But as the conversation went on, it became clear we were not saying quite the same thing. Each of us had a slightly different take on what the terms meant, and none of us were strangers to the topic.

It turns out that agreeing on being rigorous is easier than agreeing on what the words mean.

Same Terms, Different Fields

So, who was right in that thread? It turns out, it depends who you ask.

After looking into it more carefully, I realised that the same two terms, reproducibility and replicability, are used across many fields, but people do not always mean the same thing by them. That is not just a quirk, it actually reflects the kinds of questions different disciplines are used to asking.

If you are working in computational science, like data science or software development, reproducibility usually means re-running someone else’s code with the same data and getting the same output. It is about whether your pipeline works and whether it can be used again by someone else. Replicability, on the other hand, is when someone collects new data, applies the same method, and gets similar results. The focus here is often on reproducible code, documented workflows, and consistent environments.

In psychology or the life sciences, things look a bit different. Reproducibility tends to mean reanalyzing the same dataset and seeing if you come to the same statistical conclusions. Replicability usually means repeating the study with new participants, or samples, or data, and checking whether the same effect appears again. The focus is less on rerunning code and more on checking whether findings hold up when repeated.

In the social sciences, there is even more variation. Replicability often includes testing whether a finding holds in a new context, such as a different population, setting, or time. Reproducibility still involves using the same data and methods, but with more emphasis on sharing not just data, but also things like surveys, instruments, and procedures. The big question here is whether the result still holds when we move it somewhere else.

The National Academies of Sciences tried to create a shared baseline across disciplines in their 2019 report. Their definitions are:

- Reproducibility is getting the same results using the same data and the same analysis

- Replicability is getting consistent results when a study is repeated with new data and the same methods

The Turing Way, an open-source community guide to reproducible, ethical, and collaborative data science, stays close to the computational science view. It defines reproducibility as obtaining the same results when the same analysis steps are performed on the same dataset, and replicability as obtaining qualitatively similar results when the same analysis is applied to a different dataset.

Note: to be fair, The Turing Way also introduces additional concepts like robustness and generalisability, but I will not go into those here, or I will lose the thin thread of my thought. If you are interested in following up, read them here!

So while the words are shared, the meaning behind them shifts depending on the field. Sometimes the question is whether something runs again. Sometimes it is whether it works again. And sometimes it is whether it still matters in a new setting.

That is where most of the confusion starts. And, in a way, that is also where the interesting conversations begin.

What about the infographic?

Do I still like it? Yes. It helped me understand the conceptual space, and it got a useful conversation going. In some fields, the definitions I used match common usage. In others, they might not. And that is okay. For what it is worth, my version is very close to how the National Academies of Sciences define the terms. But context always matters more than labels.

What I have learned is that it is less important to be right than to recognise that the definitions vary. If you are using one of these terms, define it, even briefly. This can go a long way in avoiding misunderstandings, especially when you are working across disciplines.

A few things I took away

This whole experience, making a diagram, joining a discussion, watching it unravel slightly, and learning from the mess, left me with a few reflections:

- Definitions are not set in stone. They evolve, and that is something open science helps us see more clearly. When we work in transparent, collaborative ways, we start noticing the gaps and overlaps in how we talk about things. Where you are, what you are working on, and who you are working with can all shape what these terms mean to you

- When you use a term like reproducible or replicable, take a second to say what you mean by it

- Visuals can be powerful tools for thinking and communicating, even if they do not capture every nuance

- If you are confused by these terms, you are not alone. I gave a whole talk on the topic and still walked away with more questions than answers, but also a clearer sense of what to ask next. That feels like progress to me

TL;DR

I made an infographic.

I joined a discussion.

The discussion got a bit messy.

I learned a lot.

Open science is not about always getting things right the first time. It is about being transparent enough to revise your thinking, share what you have learned, and leave room for nuance and complexity. This post is part of that process.

For now, I will leave the diagram as it is. Maybe I will revise it later. Either way, I hope it gets people thinking, and talking.